UK retreats from mandatory digital ID for workers as privacy‑first tech gains momentum

The United Kingdom has quietly dismantled one of its most controversial digital policy ideas, abandoning plans to force every worker to use a centralized government digital ID to prove their right to work. Instead, when the national digital identity system finally appears — currently projected around 2029 — it will be offered as an option, not an obligation, and will sit alongside other forms of electronic verification and traditional documents.

Under the original proposal, employers would have been required to verify staff exclusively through a state‑issued digital credential, replacing passports, biometric residence permits and other existing paperwork. Critics argued this would effectively make a single government‑controlled ID a gatekeeper not just for employment, but potentially for many aspects of daily life.

The political cost of pushing ahead proved too high. The reversal follows months of intense criticism from across the political spectrum, civil liberties advocates and privacy campaigners. Members of Parliament such as Rupert Lowe and Reform UK leader Nigel Farage framed the plan as a fundamental threat to civil rights, warning it could create the infrastructure for mass surveillance.

Opponents repeatedly invoked the specter of an “Orwellian nightmare,” in which citizens’ sensitive data would be hoarded in one centralized database — a highly attractive target for hackers and an ideal tool for state overreach. Once built, they argued, such a system could easily “mission creep” into other areas: access to housing, opening a bank account, voting, healthcare or even social media.

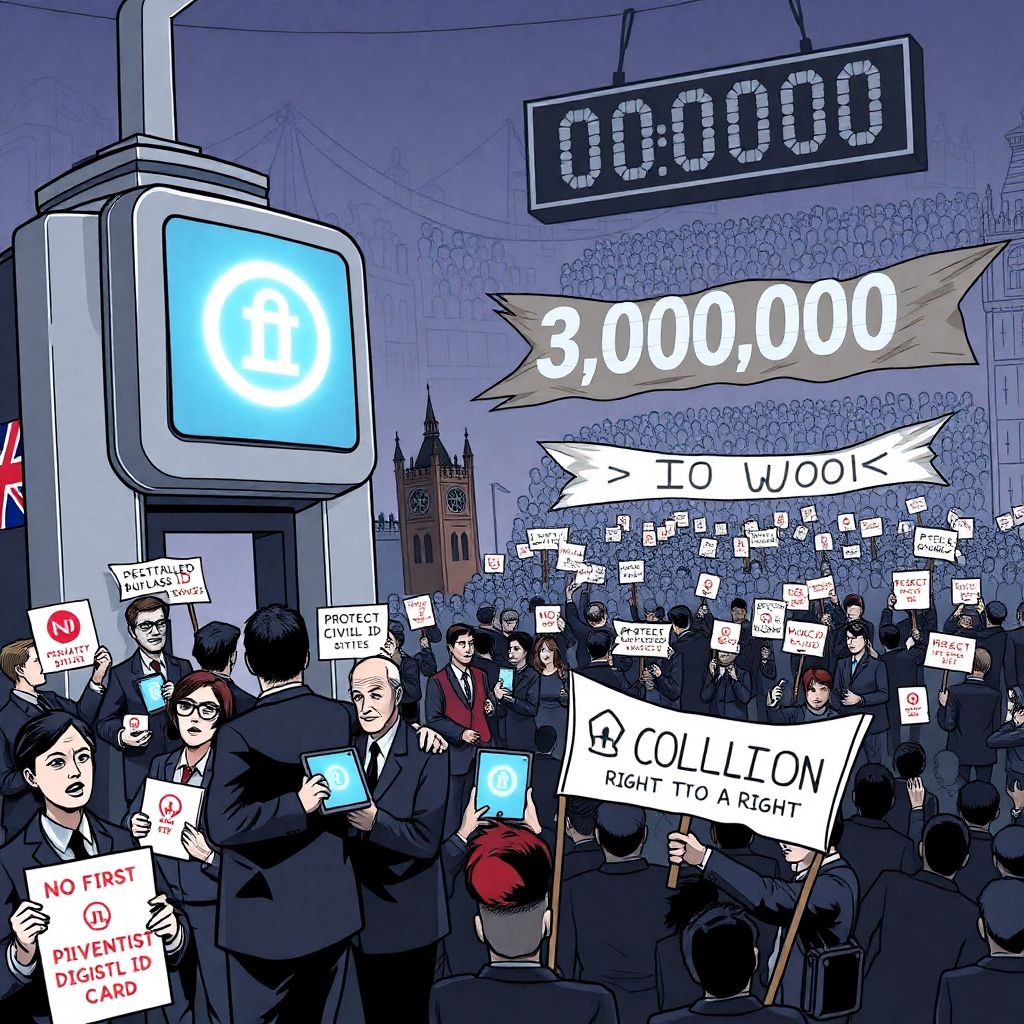

Public sentiment was similarly stark. Almost three million people added their names to a parliamentary petition opposing digital ID cards, a remarkable figure in a country where large‑scale mobilization around digital policy is usually rare. That scale of resistance turned digital ID from a technical modernization project into a lightning rod for broader anxieties about government power and data security.

The climbdown has been celebrated by critics as a major civil liberties win. Lowe publicly hailed the government’s move as the end of mandatory digital ID, while Farage framed it as a clear “victory for individual liberty” against what he described as a heavy‑handed, authoritarian approach. Their reactions underscore how identity infrastructure has become a core battleground in modern politics, rather than a niche administrative issue.

Officials insist that right‑to‑work checks themselves are not being scrapped. Employers will still have to verify that employees are legally allowed to work in the UK. The difference is in the mechanism: when the digital ID scheme launches, it will be a voluntary tool among several options, not the sole gateway to employment. In practice, that means people wary of centralized identifiers should still be able to rely on alternative electronic documents or existing forms of proof.

The UK’s partial retreat comes as other jurisdictions move in the opposite direction. Across the Channel, the European Union is pressing ahead with an EU‑wide digital identity framework and exploring a digital euro. Yet even there, lawmakers and technologists are increasingly focused on how to embed privacy protections at a structural level rather than accepting full traceability as inevitable.

Within the EU, one of the most discussed approaches is the use of zero‑knowledge proofs — cryptographic techniques that allow a person to prove something about themselves (for instance, that they are over 18, reside in a particular member state, or hold a valid license) without revealing the underlying personal data. Instead of a merchant or platform seeing your full identity, they simply receive a mathematically verifiable “yes” or “no” to a specific question.

This kind of architecture aims to reconcile two seemingly conflicting pressures: the need for compliance with regulations (such as age verification, anti‑money laundering rules, and sanctions enforcement) and the principle of data minimization, which seeks to collect and store as little personal information as possible. Rather than building giant centralized databases that contain every detail about everyone, systems can be engineered to reveal only what is absolutely necessary for a given transaction.

Decentralized identity technologies are emerging as a key alternative to state‑centric models. Instead of a single government database holding all identifiers, users keep their own credentials — often in a secure digital wallet — and selectively disclose them to services. Technologies such as verifiable credentials, decentralized identifiers (DIDs) and zero‑knowledge attestations are being developed to let people prove attributes about themselves while retaining control over where and how that information is shared.

On public blockchains, developers are experimenting with privacy‑preserving credential systems and smart contracts that can enforce rules without exposing all user data on‑chain. For example, a DeFi protocol might require proof that a user has passed a compliant KYC check or is based outside a sanctioned jurisdiction, while never publishing their name, address or full history on the ledger.

In parallel, privacy‑focused crypto tools are gaining renewed attention from users who are skeptical of both traditional financial surveillance and large‑scale data harvesting. Privacy coins such as Zcash and Monero, which use advanced cryptography to obscure transaction details, continue to appeal to those who view financial privacy as a core civil right rather than a niche concern. While regulators often associate these tools with illicit finance, many users see them as a response to increasingly invasive data collection.

Regulators, for their part, are not standing still. Proposals from policymakers, including frameworks for identity in decentralized finance and closer oversight of self‑hosted wallets, show a clear intention to weave identity and compliance directly into crypto infrastructure. Anti‑Money Laundering (AML) and Know Your Customer (KYC) rules are being revisited with an eye toward on‑chain enforcement, raising complex questions about how far surveillance should go and what technical safeguards are acceptable.

This tug‑of‑war is reshaping how identity is designed at the protocol level. On one side are those advocating for fully centralized solutions, where the state or a few large intermediaries manage identity and access. On the other are privacy advocates and technologists pushing for architectures that distribute trust, limit data collection and give individuals more control — while still acknowledging that some level of verification is necessary for things like preventing fraud and enforcing sanctions.

The UK’s decision to water down its digital ID ambitions is therefore more than a narrow bureaucratic tweak. It signals that public tolerance for tying basic rights — such as the ability to work — to a single, top‑down identifier is limited, especially when the perceived benefits are outweighed by fears of surveillance and data breaches. For governments planning similar schemes, it is a warning that technical feasibility does not guarantee social acceptance.

At the same time, the episode illustrates an emerging policy pattern: when centralized, mandatory systems provoke backlash, policymakers increasingly turn to “privacy by design” rhetoric and optional, interoperable tools to defuse opposition. The challenge will be to ensure that optional really means optional in practice, and that alternative routes do not become so inconvenient that most people have little real choice but to adopt the digital ID.

For businesses and employers in the UK, the immediate implication is a continuation of the hybrid world: a mix of traditional documents, existing electronic checks and, eventually, opt‑in digital IDs. That fragmentation carries its own risks, including inconsistent user experience, varying security standards and potential confusion about which credentials are accepted where. Industry pressure for more streamlined systems will likely continue, putting further tension on privacy safeguards.

From a broader technological perspective, the UK’s course correction strengthens the case for privacy‑preserving identity solutions that do not depend on a single centralized authority. As more services move online and as financial, social and civic life becomes increasingly digitized, the question is no longer whether digital identity will exist, but what form it will take: centralized and surveillance‑prone, or decentralized and built around data minimization.

Ultimately, the debate around digital ID, CBDCs and blockchain‑based identity tools is not just about technology. It is about power: who controls the keys to participation in the economy and society, who has access to sensitive data, and what safeguards exist against abuse. The UK’s rollback shows that public pressure can reshape that balance — and that future identity systems will be judged as much on their respect for privacy and autonomy as on their efficiency.